Some passages may contain explicit language that is inappropriate for some young readers. If you think it’s too much for you, please return to the previous step.

Some passages may contain explicit language that is inappropriate for some young readers. If you think it’s too much for you, please return to the previous step.

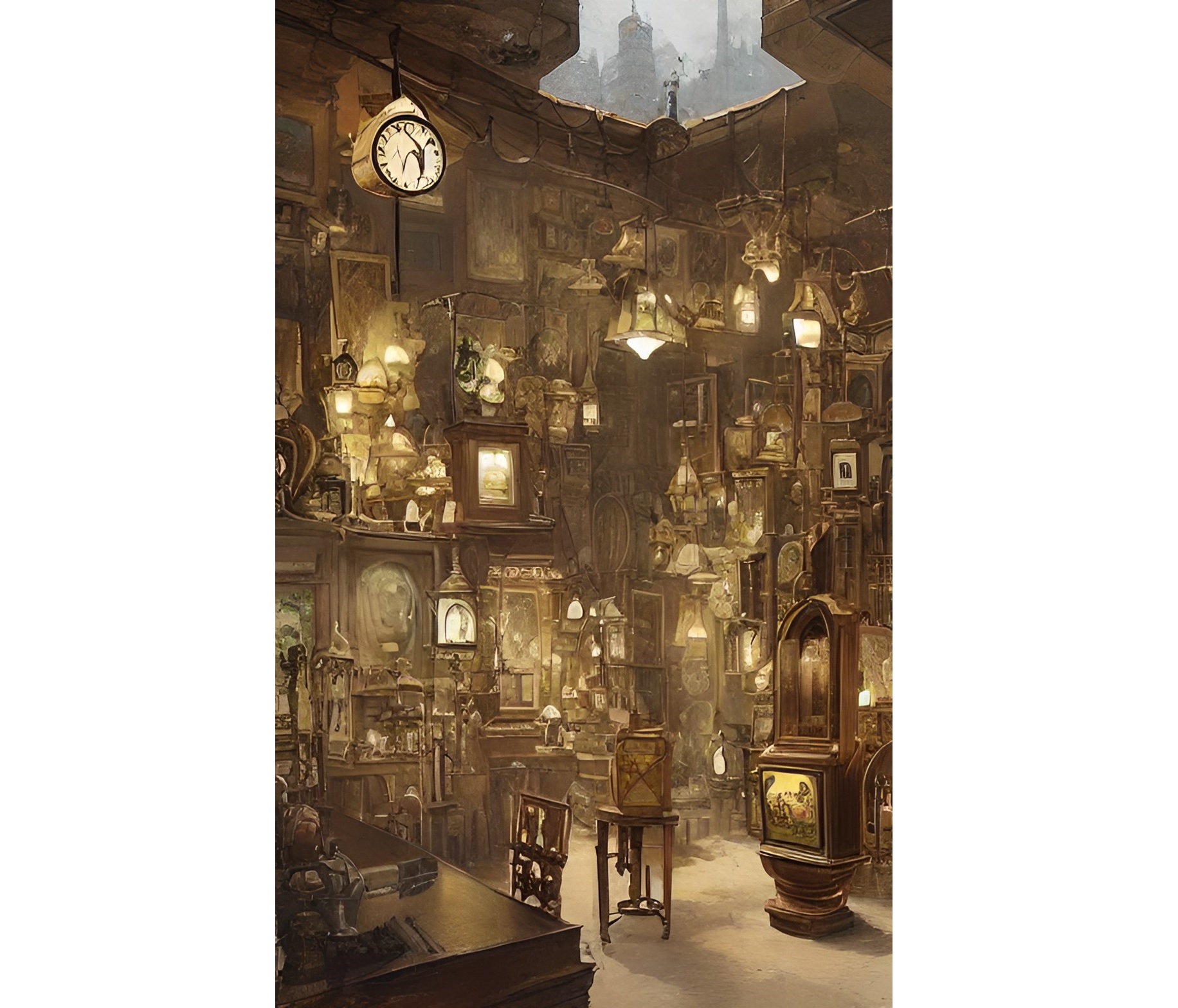

Picture by Tim ©

© 2023 - Timothy D. Capehart

Tom

dropped his bags on the floor of the entrance hall. Tiny mushroom

clouds of dust billowed up into the rays of grey-yellow sunlight that

slanted through the windows on either side of the front door behind

him. He and his sister Caryn had been raised by their grandparents in

the surprisingly bright rooms of this black stone three-story. A

decade ago as the old couple became like children themselves, Caryn

and Tom had had to take them in. Ten years the house had been left

alone; ten years the furniture had been covered, and the mirrors had

reflected only drop cloths and dust motes.

Tom

and Caryn had taken turns doing the regular maintenance on the house,

running the AC and heater in the appropriate season, keeping tabs on

the pipes in the winter, making sure the lawn service did its job.

They’d ‘kept it up’ but Tom couldn’t remember cleaning the

place in the past couple years. Now, he couldn’t believe the

accumulation of dust; everything looked slightly furry. From where he

stood, all and sundry seemed in its place. He and Caryn had left as

much as they could in the house hoping, at the start, that if it were

ready for them, their grandparents might return to it someday. That

had never happened, and Tom was home again to get things in shape for

the realtor.

It

seemed several circles were coming full turn in his life.

The

dust dried Tom's nose sufficiently to make him sneeze. His sniffles

whispered through the hollow hall like an old man's breath. He

sneezed again and remembered another arrival in that foyer.

Twenty-two years before, a newly orphaned eight-year-old boy and his

six-year-old sister had entered that same door. One of them sniffing

loudly… < The

door banged shut behind them as Grandfather brought in the last of

their things. Tom looked up at his grandmother who held his sleeping

sister. Something large had changed. He could speak the changes

because he had heard them from the mouths of so many adults in the

last weeks, but the words had seemed a foreign language until that moment. Understanding if not acceptance dawned; they would never

return to Ohio, never hold Mom’s hand, never trade tickle storms

with Dad. >

< His

grandmother no longer resembled the cheerful Mrs. Butterworth syrup

bottle. There were lines at the corners of her mouth and eyes that

didn’t accompany a smile, and there was a stoop to her shoulders

that had nothing to do with Caryn’s meager weight. >

< "You

two have come to stay with us for a while," his grandmother said

finishing her statement with a taught smile. "Tommy, get that

box and come upstairs with me.” >

< She

took him to the room he and Caryn usually shared when they visited,

"This was your father's room, but now it's yours. I cleaned it

up just for you." >

< All

the neat stuff, the pennants and baseball pictures, trophies and old

books had been taken away. The room looked unnaturally clean… >

Tom had an ulterior motive for telling Caryn he would do the cleaning and

do it alone. He planned to lose himself in the series of simple

tasks and hoped the rapid-fire sense of accomplishment would spark

his creative engine. His publisher would only accept the

I’m-working-on-it excuses for a few more months before shuffling

Tom to the back of the roster to make room for new talent. In the

year he'd been blocked, Tom had become more and more certain that he

was a one novel author, that the success of his first book had been a

fluke, and that he'd never write again.

He

left his luggage behind and walked to the back of the house. In the

kitchen, he stopped and stared out the window at the yard. Grape

vines had overtaken the red, wooden fence; they looked like verdant,

sinuous tentacles that the earth had sent up to the fence down. The

square garden plots were gone, replaced by wild growths of weeds and

the liberated descendants of domestic plants. The back walk was a

road map of cracks and veins of green. Moss and the roots of the

trees, the sun, wind, and rain had worked hard over the years to

return the garden to some semblance of its natural state. At the

center of the yard, a discarded book, grey with mildew, lay, its

sun-bleached pages open to the sky. Near it, an old bicycle seemed to

sit in rusty repose one tire bent over the pages as if reading. Great

arms of ivy had grown from the far corner of the yard to encircle the

book and the bicycle. Wrappers and papers loosened from

god-knew-where and a few soda and coffee cans dotted the brown and

green ground. Tom stared and the light yellowed. The blemishes in the

yard vanished…

< Two

children ran into the garden. A nine-year-old Tom raced past his

sister. His lengthening Dutch-boy haircut slapped either side of his

face. His clothes were clean enough, but it was apparent he'd been

around. He was wearing what his grandmother would call a ‘good day

shirt' and his adventures were written all over it. The day, by the

thinness of the white sunlight, was hardly young. He began to dig in

one of the garden squares amidst some seedling tomatoes. Caryn

followed more slowly, she was much smaller than he was and much

fairer. She shied away from the growing pile of dirt he was making

almost as if it frightened her, but she knelt down next to him. He

pretended to pick something up off the ground, something tiny beyond

sight. He dropped it into the hole he’d made and began to cover it

up… >

Tom

blinked the past from his eyes and returned to the front of the house

to pick up his bags. He had already dropped off his laptop and all

other reminders of his writing life in the small workshop attached to

the garage. He wanted to take all pressure off his dammed up

creativity. If ideas blossomed, he could take note in his journal. If

that wonderful, itchy, jittery need came back, if something real took

hold, well it was all out there in the garage waiting. For now, Tom’s

Merry Maid service was here for a house call.

~

An

hour later, he set the cleaning supplies outside the door to his old

room, and peered in. In the middle of the chamber, walls made golden

by the setting sun, the four-poster bed sat like a queen bee in the

center of her hive. Tom crossed the room, unlocked the sash window,

and gave it a tug; it stuck on the left side as if the solid,

shellacked wood wanted to keep the old, comfortable air in. Some

wiggling, pounding, and a few well placed curse words did the job.

Once it was opened and propped, he saw the holes in the screen just

big enough to let in the mosquitoes that had been the bane of his

childhood summer nights. As he went back for his bucket of cleansers

and rags, Tom was careful not to catch even a glimpse of himself in

the cracked mirror atop the wardrobe; bad luck, that…

< Tom

sat on his bed and stared at the picture of his parents. When alone

in his father's room — his room for over a year, now — Tom often

thought of his parents. Grandfather said they were in Heaven. Tom

knew what that meant; he'd learned his Sunday school lesson as well

as the next kid. He wondered if Caryn even remembered them. She and

Tom never talked about their parents. >

< Caryn

was seven and enjoyed exploring the benefits of her newly discovered

green thumb. She’d gotten over her fear of soil and digging quickly

once their grandfather offered to let her help in the garden. He said

it had never grown better than it had since she'd arrived. He'd even

let her plant a patch of her favorite plant, ivy, in the far corner

of the back yard. >

< Grandmother

said it would over-take the place before too long, but Grandfather

had poo-pooed that with a smile. Tom put the picture back in its

secret hidey-hole under the floor boards. There were pictures of his

parents through out the house, but this one was his alone. It was one

of the first photos he’d been allowed to take with the family

camera. His parents posed goofily over the kitchen table looking very

50’s-appliance-ad. >

< He

dropped the throw rug over the loose board just as Caryn, smiling

broadly with dirt under her fingernails, burst into the room to tell

him that Grandmother had finished reading the story he had written… >

Tom

picked up the shards of glass that had fallen from the mirror and

laid them carefully in the trash can he'd brought along. The story

his grandmother had finished reading that day had been some atrocious

horror tale full of flying werewolves, creeping green oozes, and

dripping blood. His grandmother had told him he had a wonderful

talent for description. She'd said she was looking forward to his

next effort which she praised just as heartily.

He had never asked Caryn what she'd been planting that day. It had been

the middle of winter, surely too cold to go outside. Perhaps if he

brought her back to the house before they sold it and they relived

their memories together, they could talk about the things they had

never shared with each other.

Tom

got the dust rags and began to go over the furniture. As he worked,

he lost himself in musings about the past.

~

In

trying to ignore the voice in his head that repeatedly told him he

had nothing new to write, Tom had passed a week in simple cleaning,

polishing, dusting, and arranging. He’d done all he could without

actually redecorating the house. As he’d worked through each of the

rooms, he’d relived a different part of his childhood. In the

kitchen there were memories of Grandma's large breakfasts before

school and of cozy Sunday dinners. In the basement, Tom remembered

his grandfather teaching him to work on lawnmower engines and build

electronic gadgets from scrap parts. In the family room, the ‘parlor’

as his grandmother had referred to it, there were nights in front of

the television with his sister and both his grandparents and bowls of

popped corn or coconut cookies and milk. All the secrets of his past

were so mundane; what did he have to write about?

Tom

cleared his mind and went through the kitchen and out the back door.

He had saved the garden until last. Even in the short time he’d

been back, the yard had changed. Hot summer sun and warm rains had

deepened the green of the wild growth and plumped-up the pages of the

abandoned book.

Tom

sat on the upper most step of the back porch, stared into the garden,

and dreamed awake…

< "Go

on," his sister's giggling voice said from the house. She

shushed the other children at his twelfth birthday party who stood

behind her, "go out to the garden, go under the ivy, Tom.” >

< Tom,

at twelve, walked down the stairs looking over his shoulder.

Grandmother stood behind his sister slowly urging him on with a

flapping wave of her hand. He walked into the garden. The ivy patch

in the far corner had begun to take over. It was where he sat and thought, where he went to

be alone and sometimes write. The whole family knew that, especially

his sister. He stopped and looked at the dark-green, heart-shaped

leaves. >

< "Under

the leaves,” Caryn said. >

< Something

silver flashed from beneath the umbrella of the leaves. Tom knelt and

looked. It was a cloth-bound notebook. Sewn into the cover was a

picture frame bisected by a white ceramic rose. On one side of the

rose was a picture from the previous summer of Tom and his sister

planting vegetables in the garden. On the other side, was a picture

of their parents doing the same thing in the garden of their old

house, the Ohio house. >

< His

sister was suddenly behind him. "Grandma helped me make it. It's

for secrets…" >

Tom

blinked the past out of his eyes again. It was in that notebook that

he'd written the first stories he’d been proud of; from his jotted

observations and ideas, realistic stories had grown. He smiled.

Thanks to Caryn, they had planted more than tomatoes and beets and

squash in the garden in the years they'd lived with their

grandparents; a lifetime of stories had their start there.

He

decided to leave the back yard as it was; nature had spent a lot of

time working to return the place to its original state. The new

owners could do with it as they pleased. They could start from

something wild and free instead of being influenced by any order he

imposed. They had the raw materials; they just had to do the work.

Tom

watched cloud shadows chase each other across the ground. In the

slight wind the fence creaked like the runners of an old rocking

chair. He let the coolness of the day lull him as he stared into the

garden. The breezes caught the drying white pages of the book, and

they fluttered in the secretive shadows beneath the dark green leaves

of ivy.

© 2023 - Timothy D. Capehart

Tommaso lasciò cadere le sue borse sul pavimento nell'atrio

d'ingresso. Piccole polveri si sollevarono dietro di lui, come

nuvolette di muffa alla luce paglierina che filtrava dalle finestre

ai lati della porta principale. Lui e sua sorella Catarina erano

stati cresciuti dai nonni nelle stanze, sorprendentemente luminose,

di questa casa di tre piani in pietra scura. Dieci anni fa, quando i

due anziani tornarono bambini, Catarina e Tommaso li avevano accolti

con loro. La casa di famiglia era stata lasciata a sé stessa per

dieci anni; anni in cui i mobili erano stati coperti e gli specchi

avevano riflesso solo teli e moti di polvere.

Tommaso

e Catarina si erano alternati nelle operazioni di cura della casa,

facendo funzionare l'aria condizionata e il riscaldamento a seconda

della stagione, controllando le tubature in inverno e assicurandosi

che il Servizio di manutenzione del prato, di fronte alla casa,

svolgesse il lavoro assegnato. Nella casa avevano ‘gestito tutto’

ma Tommaso non riusciva a ricordare di averla ripulita negli ultimi

anni. Non poteva credere all'accumulo di polvere; tutto pareva come

leggermente lanoso. Da dove si trovava, tutto sembrava

al suo posto. Avevano lasciato il più possibile in casa sperando

inizialmente che, se fosse stata pronta per loro, un giorno i nonni

sarebbero potuti tornare. Ma ciò non era mai successo e Tommaso era

di nuovo lì per mettere le cose in ordine per l'agente immobiliare.

Era

come se molte esperienze si stessero chiudendo nella sua vita.

Per

via della polvere, Tommaso sternutì. Il rumore risuonò attraverso

il vuoto dell'atrio, come il sospiro di un anziano. Ancora un altro

starnuto, e improvvisamente fu catapultato in un altro ricordo.

Ventidue anni prima lui e Catarina, piccoli orfani, erano entrati

dalla stessa porta. Uno di loro starnutì rumorosamente...

< La

porta sbatté dietro di loro mentre il nonno portava l'ultima parte

delle loro cose. Così Tommaso alzò gli occhi verso la nonna che

teneva in grembo la sorella addormentata. Qualcosa di grande era

cambiato. Poteva identificare i cambiamenti perché li aveva sentiti

così tante volte nelle ultime settimane ma, fino a quel momento, le

parole erano sembrate incomprensibili. Capì, se non l'accettò; non

sarebbero mai più tornati in Ohio, non avrebbero più tenuto la mano

della mamma, non avrebbero più scherzato con il papà. >

< Sua

nonna non somigliava più alla 'Mrs. Butterworth' dell'allegra

bottiglia di sciroppo. Aveva delle rughe agli angoli della bocca e

degli occhi, rughe che non accompagnavano un sorriso e aveva le

spalle curve, nonostante il peso leggero di Catarina. >

< "Verrete

a stare da noi per un po'," aveva detto con un sorriso teso.

"Tommi, prendi quella scatola e vieni su con me." >

< Lo

portò verso la stanza che aveva condiviso con Catarina durante le

loro visite "Questa era la stanza di tuo padre, ma ora è la

tua. L'ho sistemata apposta per te." > < Tutte

le cose ordinate, le bandiere e le foto del baseball, i trofei e i

vecchi libri erano stati rimossi. La stanza sembrava stranamente

pulita... >

Tommaso aveva un secondo motivo per dire a Catarina che si sarebbe occupato

della pulizia da solo. Aveva in mente di perdersi nei semplici gesti

e sperava che il senso di realizzazione avrebbe riacceso il suo

motore creativo. Il suo editore avrebbe tollerato solo per un paio di

mesi ancora le scuse del tipo "ci sto lavorando" prima di

spostare Tommaso in fondo all'elenco per fare spazio a nuovi talenti.

Durante quell'anno di blocco creativo, era diventato sempre più

convinto di essere l'autore di un solo romanzo, che il successo del

suo primo libro fosse stato solo un caso fortunato e che non avrebbe

mai più scritto.

Lasciò

le valigie e si diresse verso il retro della casa. Si fermò in

cucina e guardò il cortile fuori dalla finestra. Le viti rampicanti

avevano preso il sopravvento sulla rossa recinzione in legno;

sembravano tentacoli verdi e sinuosi che la terra aveva mandato verso

la recinzione. I piccoli orti quadrati erano scomparsi, sostituiti da

una crescita selvaggia di erbacce e di piante domestiche che avevano

riconquistato il loro spazio, liberate. Il sentiero sul retro era una

mappa di crepe e vene di verde. Il muschio e le radici degli alberi,

il sole, il vento e la pioggia avevano lavorato duramente nel corso

degli anni per restituire al giardino una sorta di stato naturale. Al

centro del cortile, un libro abbandonato, grigio di muffa, le pagine

sbiadite dal sole spalancate verso il cielo. Accanto, una vecchia

bicicletta sembrava seduta in un riposo arrugginito, una ruota

piegata sulle pagine come se stesse leggendo. Grandi bracci di edera

erano cresciuti dall'angolo lontano del cortile, per circondare il

libro e la bicicletta. Cartacce e lattine di soda e caffè, chissà

da dove, sparsi sul bruno terreno. Tommaso osservava il tutto, mentre

la luce imbruniva. Le imperfezioni del cortile svanirono...

< I due bambini corsero in giardino. Tommaso, di nove anni, superò di gran fretta la sorella. Aveva i capelli alla maschietto che gli sbattevano

ai lati del viso. I vestiti erano ancora abbastanza puliti, ma si

notava che aveva giocato. Indossava quello che sua nonna avrebbe

chiamato una ‘maglietta per i giorni buoni’ e le sue avventure

erano scritte ovunque. La giornata, dalla debole luce bianca, era

ormai avanzata. Iniziò a scavare in uno dei piccoli orti, tra alcuni

pomodori appena piantati. Catarina seguì, più lentamente; era molto

più piccola di lui e dalla carnagione molto più chiara. Si

allontanò dalla pila di terra che lui stava facendo, quasi come se

la spaventasse, ma gli si inginocchiò accanto. Lui fece finta di

raccogliere qualcosa da terra, qualcosa di minuscolo e invisibile. Lo

lasciò cadere nel buco che aveva fatto e cominciò a coprirlo... >

Socchiuse

gli occhi come per scrollarsi il passato e tornò di fronte alla casa

per prendere le sue borse. Aveva già lasciato il computer e ogni

altro ricordo legato alla sua vita da scrittore nel piccolo

laboratorio annesso al garage. Voleva togliersi ogni pressione dalla

sua bloccata creatività. Se l'ispirazione fosse sbocciata, avrebbe

preso nota nel suo diario. Se quella meravigliosa, irrequieta e

nervosa esigenza fosse tornata, se qualcosa di reale avesse preso

forma, tutto era lì nel garage ad aspettarlo. Per ora, il servizio

di pulizia ‘Merry Maid’ di Tommaso era lì per fare visita alla

casa.

~

Un'ora

dopo, lasciò i detergenti fuori dalla porta della sua vecchia stanza

e sbirciò all'interno. Nel centro della stanza, illuminata dalla

luce del tramonto, il letto a baldacchino era posizionato nel mezzo,

come un'ape regina nel suo alveare. Tommaso attraversò la stanza,

sbloccò la finestra a battente e le diede una spinta; si incastrò

sul lato sinistro come se il solido e laccato legno volesse

trattenere l'aria vecchia e confortante nella stanza. Riuscì a

sbloccarla con un pò di sforzo e qualche imprecazione ben piazzata.

Una volta aperta e fissata, vide dei buchi nella zanzariera; erano

abbastanza grandi da far entrare le zanzare che avevano tormentato le

notti estive da bambino. Mentre tornava indietro per prendere il

secchio con detergenti e i panni, cercò di evitare persino il suo

sguardo allo specchio crepato sopra l'armadio; portava sfortuna,

quello...

< Tommaso

si sedette sul suo letto e fissò la foto dei suoi genitori. Quando

era solo nella stanza di suo padre —

la

sua stanza da oltre un anno ormai —

pensava spesso ai suoi genitori. Il nonno diceva che erano in

Paradiso. Sapeva cosa significasse; aveva imparato la lezione

alla scuola domenicale come tutti gli altri bambini. Si chiedeva

anche se Catarina li ricordasse ancora. Lei e Tommaso non avevano mai

parlato dei loro genitori. >

< Catarina

aveva sette anni e si divertiva a esplorare i vantaggi del suo appena

scoperto pollice verde. Aveva superato in fretta la sua paura del

terreno e degli scavi una volta che il nonno le aveva offerto di

aiutarlo nell'orto. Diceva che non era mai cresciuto meglio di quanto

non avesse fatto da quando era arrivata lei. Le aveva persino

concesso di coltivare un pezzo di terra con la sua pianta preferita,

l'edera, nell'angolo più lontano del cortile. >

< Nonna disse che avrebbe preso il sopravvento prima o poi, ma il nonno

sorridendo aveva respinto l'idea. Tommaso rimise la foto nel suo

nascondiglio sotto le tavole del pavimento. C'erano foto dei suoi

genitori in tutta la casa, ma questa era solo sua. Era una delle

prime foto che gli era stato permesso di scattare con la macchina

fotografica di famiglia. I suoi genitori posavano in modo buffo sopra

il tavolo della cucina, sembravano proprio usciti da un annuncio di

elettrodomestici degli anni '50. >

< Lasciò

cadere il tappeto sopra la tavola mentre Catarina, con un gran

sorriso e le unghie sporche di terra, entrò nella stanza per dirgli

che la nonna aveva appena finito di leggere il racconto che aveva

scritto... >

Raccolse

i cocci di vetro che erano caduti dallo specchio e li pose con cura

nel cestino che aveva con sé. La storia che sua nonna aveva finito

di leggere quel giorno era un terribile racconto dell'orrore con lupi

mannari volanti, melme verdi striscianti e fiumi di sangue. Gli aveva

detto che aveva un talento meraviglioso per le descrizioni. Aveva

detto che non vedeva l'ora del suo prossimo racconto, elogiando il

suo lavoro con sincerità.

Non

chiese mai a Catarina cosa avesse piantato quel giorno. Era stato nel

bel mezzo dell'inverno, troppo freddo per uscire. Forse, se l’avesse

portata nella casa prima di venderla e avessero rivissuto insieme i

ricordi, avrebbero parlato di cose mai condivise prima.

Tommaso

iniziò a spolverare i mobili. Mentre lavorava si perse in

riflessioni sul passato.

~

Nel

tentativo di ignorare la voce nella sua testa che gli ripeteva di non

aver niente di nuovo da scrivere, Tommaso aveva passato una settimana

a fare pulizie, lucidare, spolverare e sistemare. Aveva fatto tutto

quel che poteva senza stravolgere nulla. Mentre lavorava, in ogni

stanza, riviveva una parte diversa della sua infanzia. In cucina

c'erano ricordi delle abbondanti colazioni della nonna prima della

scuola e delle accoglienti cene della domenica. In cantina ricordava

suo nonno che gli insegnava a lavorare sui motori dei tagliaerba e a

costruire apparecchiature elettroniche con pezzi di recupero. Nella

sala familiare, il ‘salotto’ come sua nonna l'aveva chiamato,

c'erano le serate davanti alla televisione con la sorella e i nonni,

ciotole di popcorn o biscotti al cocco e latte. Tutti i segreti del

suo passato erano così comuni; cosa avrebbe potuto scrivere?

Tommaso

liberò la mente e attraversò la cucina, uscendo dalla porta sul

retro. Aveva lasciato il giardino per ultimo. Anche nel breve periodo

in cui era tornato alla casa, il cortile era cambiato. Il caldo sole

estivo e le piogge calde avevano esasperato il verde della selvaggia

vegetazione e gonfiato le pagine di quel libro abbandonato.

Allora

si sedette sul gradino più alto della veranda, sul retro, guardando

fisso il giardino e sognando ad occhi aperti...

< "Avanti,"

disse la voce sorridente di sua sorella dalla casa. Zittì gli altri

bambini, che stavano dietro di lei, alla festa per il dodicesimo

compleanno del fratello. "vai in giardino, vai sotto l'edera,

Tommi." >

< Aveva

dodici anni, Tommaso scese le scale guardando dietro di sé. La nonna

stava dietro sua sorella, incoraggiandolo lentamente con un gesto

della mano. Arrivò in giardino. Il groviglio di edera nell'angolo

più lontano aveva iniziato a prendere il sopravvento. Era lì che si

sedeva a pensare, andava lì per stare da solo e qualche volta

scrivere. Tutta la famiglia lo sapeva, soprattutto sua sorella. Si

fermò e guardò le verdi foglie a forma di cuore. >

< "Sotto

le foglie," disse Catarina. >

< Qualcosa

di argenteo balenò sotto l'ombrello di foglie. Tommaso si chinò per

guardare. Era un quaderno rilegato in tessuto. Cucito nella copertina

c'era una cornice per foto divisa da una rosa di ceramica bianca. Da

un lato della rosa c'era una foto dell'estate precedente di Tommaso e

sua sorella che piantavano verdure nell'orto. Dall'altro lato, c'era

una foto dei loro genitori che facevano la stessa cosa nell'orto

della loro vecchia casa, quella dell'Ohio. >

< Sua

sorella fu improvvisamente dietro di lui.

“nonna

mi ha aiutato a farlo. È per i segreti..." >

Tommaso

scosse via il passato dagli occhi ancora una volta. Era in quel

quaderno che aveva scritto le prime storie di cui andava fiero; dai

suoi appunti e idee scarabocchiati erano cresciute storie

realistiche. Allora sorrise.

Grazie

a Catarina, nell'orto avevano piantato più che semplici pomodori,

barbabietole e zucche negli anni che avevano vissuto con i nonni; lì

era iniziata una vita intera di storie.

Decise

di lasciare il cortile così com'era; la natura aveva impiegato molto

tempo per restituire il luogo al suo stato originale. I nuovi

proprietari avrebbero potuto fare ciò che volevano. Avrebbero potuto

partire da qualcosa di spontaneo, libero, invece di essere

influenzati dall'ordine che lui aveva imposto. Avevano le materie

prime; dovevano solo lavorarci un pò.

Tommaso

guardò le ombre delle nuvole inseguirsi sul terreno.

Dolci ventate fecero scricchiolare la recinzione, come i pattini di

una vecchia sedia a dondolo. Si lasciò cullare dalla freschezza

della giornata e guardò il giardino. La brezza catturava le bianche

pagine del libro che, asciugando, si agitavano in segreto, sotto le

foglie scure dell'edera.

Picture by Laura ©

© 2023 - Laura A. Ferrabino

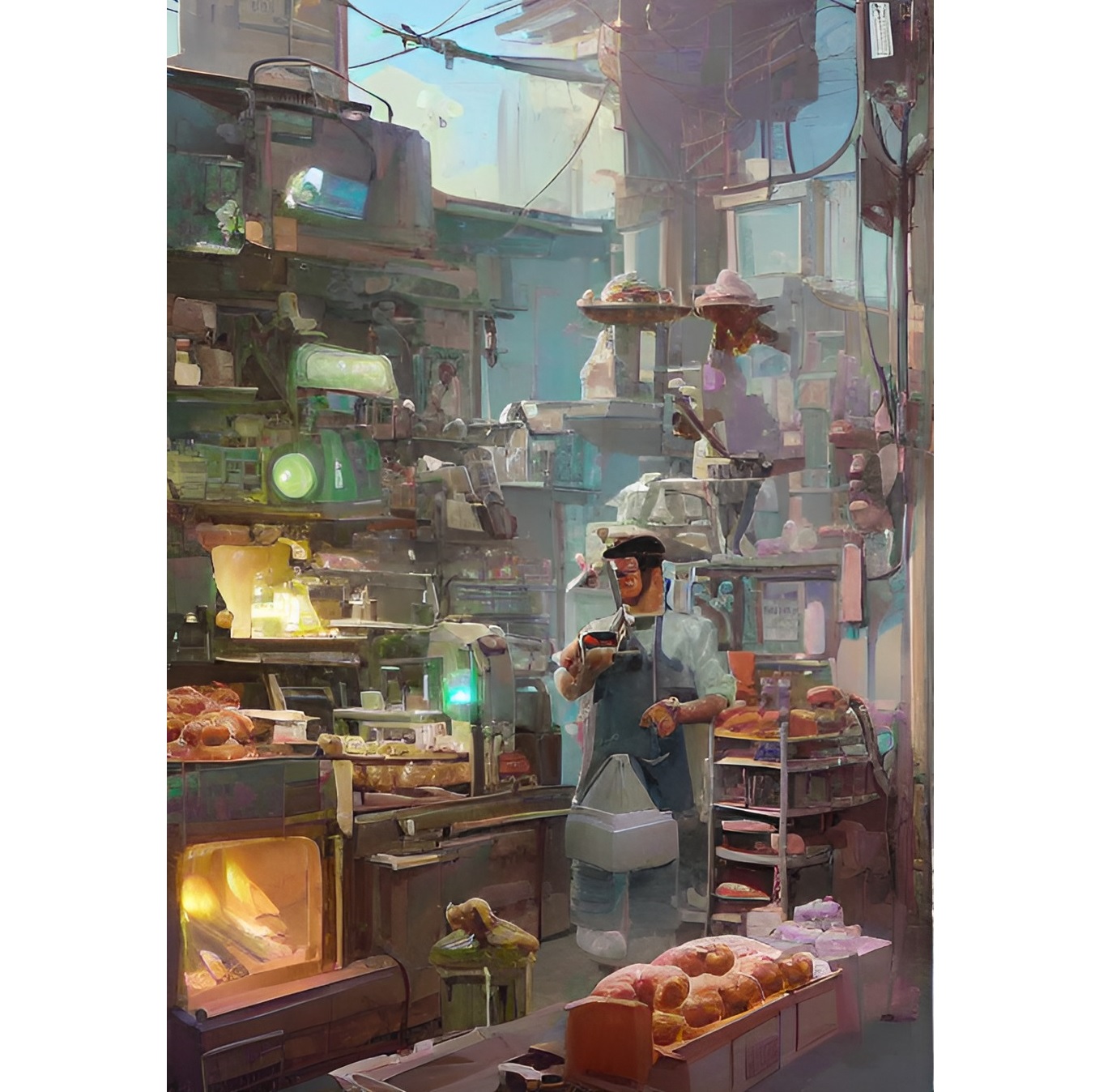

Once

upon a time, there was a Hen and a Cow.

Every

night, they would meet in the farmyard, raise their heads, and track

the transient motions of the stars: bright balls, moving crazily

through a big pot of purple sauerkraut. The Stars!

Cow

saw the stars as big and close, Hen saw ‘em as small and far away.

Every

evening was the same.

Then

something happened... One night, the moon was fuller and brighter

than usual, and its light didn't allow anything else to be seen. Only

the big, incredibly strong silvery super ball, taking light from

everything and everyone.

So,

the Cow and Hen climbed the barn ladder to see it better. But no such

luck! They could see nothing except the big and majestic ball.

It

looked like a flake of butter!

And

that is how Cow and Hen agreed. They finally saw the same thing: a

balloon hung in the Universe!

Size

and distance no longer mattered...

And

they all lived happily ever after.

© 2023 - Laura A. Ferrabino

C'erano

una volta una Gallina e una Mucca.

Tutte

le notti si incontravano nel cortile della fattoria, alzavano la

testa e seguivano i moti transitori delle stelle: palline luminose,

come impazzite, in un grande minestrone di crauti viola. Le

Stelle!

La

mucca le vedeva grandi e vicine, la gallina piccole e lontane.

Tutte

le sere così.

Capitò

un fatto... Una

notte la luna fu più piena e più luminosa del solito e la sua luce

non lasciava intravedere altro. Solo la grande,

luminosissima

super-palla argentata, che toglieva luce a tutto e tutti.

Allora

Mucca e Gallina salirono sulla scala del fienile per vederci meglio.

Ma niente da fare! Non

si vedeva altro che la grossa e maestosa palla.

Pareva

un fiocco di burro!

Fu

così che Mucca e Gallina si accordarono. Videro finalmente la stessa

cosa: un pallone appeso all'Universo. Dimensione e distanza non

contavano più...

E

tutti vissero felici e contenti.

Picture by Tim ©

© 2023 - Timothy D. Capehart

I

pull the door to behind myself and step out into the night air. Any

more pacing on those hollow, hard-wood floors would have deafened me.

Another few moments in the empty closeness of my room, and I would

have slipped into insanity. The house is as it was before. No big

changes have taken place despite the fact that one of its occupants

is missing. I have been walking all night in and out of the house. If

Mom and Dad were awake for it all, I would have driven them crazy.

I

descend the AstroTurf covered steps and head off in the same

direction I walked earlier this evening. I do my best to concentrate

on my surroundings and not my destination.

The

moon, ochred by the clouds of tomorrow’s rainstorm, hangs low in

the sky. Thunderless heat-lightning flashes sporadically in the east.

Occasionally purple headlights brighten the road between the pools of

peach glow from buzzing, corner street lamps, but mostly I am left in

with just the moonlight. On either side of me, dark-windowed houses

face off as I walk between them. Dickens was right; each house seems

a mystery. But inside those houses live the bigger mysteries, the

people I supposedly know… the people who think they know me. A short

distance down the street a figure passes from the curb to a house. It

is greeted by lights and the friendly yapping of a dog. How many

people go home willingly to dark, empty houses? Noticing I've

stopped walking, I begin, once again, to step off the oblong blocks

that make up the curb.

In

the light on the next corner, I stop and sit. Listening to the hum of

the streetlight's carbon-arc harmonizing with the night insects, I

flick the moth carcasses scattered at the base of the lamppost into

the street. Memories of surprising clarity surface. I remember

catching spiders and drowning them in the bathroom sink with the

blatant disregard for life evinced by some children.

I remember

cloudless-blue, hazy summer days in the back yard with my sister,

Sue. Using Tupperware bowls, we would catch bees off of Mom's

honeysuckle. We'd listen to the sweet humming coming from within the

bowl until the bee dropped and its humming stopped. When all the bees

in their bowls had ceased their buzzing, Sue and I would empty the

bowls and race to capture more unsuspecting bumblers.

Headlights

flash bright in my eyes. A convertible full of kids runs the stop

sign on the opposite corner. The radio is blaring, and half the

occupants are hanging out of the car. The other half are ignoring

each other to talk into their phones. Someone honks the horn as the

car goes by. I turn to watch the tail lights recede. They slowly wink

out one at a time. I couldn’t even say if knew anyone in the car.

One year at college and all this seems as remote as those memories of

summer afternoons.

Resuming

my walk, I follow the convertible's stingingly dry fumes and head out

of town. A phone rings in one of the dark houses. Bad news. Mom would

always worry through three rings before answering the phone late at

night. She was rewarded with the anticipated tragedy three times.

I

remember being awakened by the phone at midnight fourteen years or so

ago. There was a pause and some susurrate argument from the next

room. A few moments later Mom came into my room. Blinking her blue

eyes more often than usual, she told me Grandad had passed away. She

said she and Dad were going to see him off. I was to stay at the

neighbors', but Sue, two years my senior, would go with them. They

left that night and were back in three days. Nothing much in our

day-to-day changed.

As

I walk through the almost visible moisture in the air, my shirt

clings to me as if it were soaking wet. I dry my forehead with my

sleeve. My memories of Grandad are misty-edged. They swirl up in

quick succession: days in the park, water fights with hissing hoses

in the back garden, exploring the old house he lived in. I know I

spent time with Grandad and enjoyed it, but I don't remember tears

ever falling when he was gone. I guess I was too young when it

happened and too used to the idea of his absence when I was old

enough to understand what had happened.

The

repetitive, melodious chirping of the katydids and crickets reminds

me once more of the bees. I remember the feeling of the Tupperware

against each ear and the feeling of power I had over those tiny

insects. I remember how angry, how sad and angry, I was when Sue

wouldn't trap bees with me anymore.

She

said she wouldn't play because bee-trapping was a baby’s game. She

was too old for such little kid stuff. I knew her better than that.

Even though I was only nine, I remember thinking that the truth was

that she didn’t want to hurt the bees.

I

stop. End of the road. The street turns to gravel and a low fence

bars my way. I step over the fence and into the field. The taller

grasses poke their stalks above the ground fog that has come in off

the pond. Walking as I did a few hours ago through the field, I

listen to the flowers and heavy-headed grasses knocking hollowly

against my shoes. A breeze whiffs in from the east. Cooling the air,

it carries with it a cold humidity, that promise-of-rain scent.

The

breeze makes the ground fog writhe for a few moments before

dispersing it. There is the gunmetal-taste of ionization in my mouth.

For once the weatherman is right, we’ll have a storm.

The

fog is gone; I can make out the dead, brown squares of grass this

year's carnival left behind. I smile; carnival nights were always the

social event of the summer. Sue made it a point to take me to the

carnival each year. We, of course, rode all the rides and saw all the

shows, but the highlights of the evening were the atmosphere and the

food. Each year I noticed something new about the carnival. There

were strange people with strange mannerisms. Smells of food,

excitement, fear, and sweat swirled around us in the heavy air of

summer's-end. Sue and I would stuff ourselves on batter-dipped

mushrooms and shrimp. There would always be numerous candy apples and

chocolate-covered bananas, and we never left the carnival without

getting a huge bag of cotton candy. When I was fifteen, we each took

our first dates with us. That night we got home a little too late for

Mom's liking, but before she could get up speed in her scolding, the

phone rang. It was after midnight. She worried through three rings

before snatching the phone from its cradle. Her breath caught in her

throat, and we knew it was bad news. Grandpap, her father, had had a

heart attack. That time I went to the funeral.

I

loved Grandpap, at least I think I did. While he was alive, I thought

I wouldn't be able to live without him. He took me fishing and

camping. He taught me to watch animals, especially the birds. I sat

in the church during his memorial service thinking over and over that

I couldn't believe he was gone. All around me women were crying, and

the men looked as if they were doing everything they could not to. I

didn't think it was seemly for me to cry, so I didn't. At the grave

side, I watched squirrels chase each other among the headstones.

Leaves rattled and fell in yellow showers as the wind blew. Winter

was on its way. A huge dark wedge of birds split the sky over head.

They were still migrating. I realized the world would get along fine

even though Grandpap was dead.

Sue

was full of sympathy for me. She knew Grandpap and I were close. She

told me, in private, that it was okay for me to cry. She said she

knew I was all broken up inside. I told her I was fine and life,

before too long, would go back to normal. She seemed horrified and

didn't talk to me for the rest of the day.

I

stand before the gates. The insects are silent. I was here not more

than two hours ago, but I walked on by and went home. Now, I feel I

have to go in. The black, wrought-iron spikes of the gates and fence

jab into the sky. Why do they lock cemetery gates? Those that want to

get in get in, and those already in can’t get out. I guess the

caretaker has to do more than just mow the grass.

I'm

careful not to catch my clothing as I climb over with the aid of a

gnarled oak tree. A rumble of thunder sounds as I land with a jolt on

the other side. My feet know the way; I have walked it many times

over the past year. "Susanna Teal," the stone reads.

Beneath that are birth and death dates. A year ago Mom got a third

late-night call. Sue had had an accident driving home from some

party. She hadn't made it to the hospital.

I

want desperately to say something, but I have the feeling the wind,

which has been growing in strength, would whip away any words I might

say. Who would I be saying them for anyway? I know I loved Sue. At

least I felt for her what has passed for love in my life. Mom used to

say I worshipped the ground Sue walked on, but I didn't cry at her

funeral. And my life has gone on since.

Suddenly

I feel sick. What little I ate before I began walking threatens to

come up. I stare at the stone and the oblong mound of grassy dirt.

I

am getting along.

My

stomach heaves, and I run bent double for the gate as the rain begins

to fall. There is a quiet roar as my shirt, caught on one of the

spike points, rips. I am blinded by wind and rain as I run from that

stone, from those dark gates, toward a watery blur of light across

the field.

© 2023 - Timothy D. Capehart

Chiudo

la porta dietro di me ed esco all'aria notturna. Continuare a

camminare su quei pavimenti di legno duro e vuoti avrebbe assordato

chiunque. Altri pochi istanti nella solitudine della mia stanza e

sarei impazzito. La casa è rimasta come prima. Nessun grande

cambiamento, nonostante uno dei suoi occupanti sia scomparso. Ho

camminato tutta la notte, dentro e fuori dalla casa. E se mia madre e

mio padre fossero stati svegli per tutto il tempo, li avrei fatti

impazzire.

Scendo

le scale, coperte di erba sintetica ‘AstroTurf’, e mi dirigo

nella stessa direzione di questa notte. Faccio del mio meglio per

concentrarmi sugli ambienti circostanti e non sulla mia destinazione.

La

luna, ingiallita dalle nuvole del temporale di domani, è bassa in

cielo. C'è un lampeggiare silenzioso di fulmini illuminato dalla

calura occasionalmente a Est. E occasionalmente fari viola illuminano

la strada tra le pozzanghere color pesca, dai lampioni, agli angoli

della strada, ma sono solo e per lo più con la luce della luna. Da

entrambi i lati rispetto a me, case con finestre scure si sfidano

mentre le attraverso. Dickens aveva ragione; ogni casa sembra un

mistero. Ma all'interno di quelle case vivono i misteri più grandi,

le persone che probabilmente conosco... le persone che pensano di

conoscermi. A breve distanza lungo la strada, una figura attraversa

il marciapiede dirigendosi verso un'abitazione. Ad accoglierla alcune

luci e i guaiti festosi di un cane. Quante persone tornano volentieri

nelle proprie case buie e vuote? Notando che ho smesso di camminare,

ricomincio, calpestando i lunghi blocchi del marciapiede.

Mi

fermo e mi siedo sotto la luce, all'angolo successivo. Ascolto il

ronzio della lampada 'ad arco’ che si armonizza con quello degli

insetti notturni e scosto i cadaveri delle falene caduti alla base

del lampione. Affiorano memorie di sorprendente chiarezza. Ricordo di

aver catturato ragni e di averli annegati nel lavandino del bagno,

con quel disprezzo sfacciato per la vita di certi bambini. E

ricordo le terse giornate estive e quelle nebbiose nel cortile di

casa con mia sorella, Sue. Catturavamo le api dal gelsomino di mamma

con dei contenitori 'Tupperware'. Ascoltavamo quel delicato brusio

che usciva dalla scatola finché l'ape cedeva, e il mormorio si

fermava. E quando tutte le api nelle loro ciotole avevano smesso di

ronzare, io e Sue svuotavamo le ciotole e ci precipitavamo a

catturare altri ingenui visitatori.

I

fari si illuminavano intensamente nei miei occhi. Una cabriolet piena

di ragazzi trascura il segnale di stop all'angolo opposto. La radio è

alta, e metà degli occupanti si sporgono fuori dalla macchina. Gli

altri si ignorano a vicenda per parlare al telefono. Qualcuno suona

il clacson mentre la macchina passa. Mi giro per guardare i fanali di

coda che si allontanano. Si spengono lentamente una alla volta. Non

saprei nemmeno dire se conoscevo qualcuno nella macchina. Un anno al College e tutto sembra così lontano come quei ricordi di pomeriggi

estivi.

Riprendendo

a camminare, seguo la scia della cabriolet e mi dirigo fuori dalla

città. Un telefono squilla in una delle case. Cattive notizie. Mia

mamma si è sempre preoccupata nei tre squilli prima di rispondere al

telefono durante la notte. Ed è stata sempre premiata con la

tragedia, per ben tre volte.

Ricordo

di essere stato svegliato dal telefono a mezzanotte circa quattordici

anni fa. C'è stata una pausa e una discussione sussurrata nella

stanza accanto. Poco dopo, mia madre è entrata nella mia camera.

Sbattendo i suoi grandi occhi blu più del solito e dicendomi che il

nonno era mancato. Ha detto che lei e papà sarebbero andati a

salutarlo. Avrei dovuto stare dai vicini ma Sue, due anni più grande

di me, disse che sarebbe andata con loro. Sono quindi partiti quella

stessa notte e tornati tre giorni dopo. Ma non molto è cambiato da

allora nella nostra vita quotidiana.

Mentre

cammino nella quasi invisibile umidità, la camicia mi si

appiccica come fosse bagnata. Mi asciugo la fronte con una manica. I

ricordi del nonno sono sfumati. Si susseguono rapidamente: giorni al

parco, battaglie d'acqua con innaffiatori che sibilano in giardino,

esplorazioni nella vecchia casa in cui viveva. So che ho trascorso

del tempo con lui e che mi sono divertito, ma non ricordo lacrime

versate quando se ne è andato. Immagino che fossi troppo giovane

quando è accaduto e troppo abituato all'idea della sua assenza

quando ero abbastanza grande per capire cosa fosse successo.

Il

frinire armonico e ripetitivo dei grilli mi ricorda ancora una volta

le api. Ricordo la sensazione del 'Tupperware' nelle orecchie e la

sensazione di potere assoluto che avevo su quei piccoli insetti.

Ricordo quanto fossi arrabbiato, quanto fossi triste e arrabbiato,

quando Sue non volle più catturare le api con me. Diceva che non

avrebbe giocato perché catturare api era un gioco da bambini. Era

troppo grande per quelle cose. La conoscevo meglio di così. Anche se

avevo solo nove anni, ricordo di aver pensato che la verità fosse

che lei non voleva far male alle api.

Mi

fermo. Fine della strada. La strada diventa ghiaia e una bassa

recinzione mi sbarra il passaggio. Scavalco la recinzione ed entro in

un campo. Le erbe più alte sporgono sopra la nebbia che arriva dal

laghetto. Camminando come ho fatto qualche ora fa, attraverso il

prato e ascolto i fiori e le erbe calpestate, come fosse un sordo

picchiettio contro le scarpe. Arriva vento da Est. Raffreddando

l'aria, trasporta con sé un'umidità fredda, quell'odore di promessa

pioggia.

Fa

contorcere la nebbia a terra per alcuni istanti prima di dissiparla.

Ho un sapore metallico in bocca. Per una volta il meteorologo ha

ragione, è in arrivo un temporale.

La

nebbia è sparita; riesco a distinguere lembi di erba secca della

Fiera di quest'anno, il Carnevale. Sorrido; le serate di Carnevale

sono sempre state l'evento sociale dell'estate. Sue faceva in modo di

portarmi alla fiera ogni anno. Noi andavamo, ovviamente, su tutte le

giostre e guardavamo tutti gli spettacoli, ma le attrazioni della

serata erano di certo l'atmosfera e il cibo.

Ogni

anno notavo qualcosa di nuovo in Fiera. C'erano persone strane che

facevano cose ancora più strane. Profumi di cibo, fermento, paura e

sudore si mescolavano nell'aria densa di fine estate. Io e Sue ci

rimpinzavamo di funghi e gamberi in pastella. C'erano sempre tante mele caramellate e banane ricoperte di cioccolato, e non lasciavamo

mai la Fiera senza prendere una gigantesca confezione di zucchero

filato. Ricordo di aver avuto quindici anni quando portammo con noi

anche i nostri primi fidanzatini. Quella sera siamo tornati un po'

troppo tardi secondo la mamma, ma prima che potesse iniziare a

rimproverarci, il telefono aveva squillato. Era passata la

mezzanotte.

Si

era preoccupata per i tre squilli prima di afferrare il telefono. Il

respiro le si era bloccato in gola, e già sapevamo che sarebbero

state brutte notizie. Il nonno, suo padre, aveva avuto un attacco di

cuore. Quella volta sono andato al funerale.

Amavo

il nonno, o almeno credo di averlo fatto. Quando era in vita, pensavo

di non poter vivere senza di lui. Mi portava a pescare e a fare

campeggio. Mi insegnò a osservare gli animali, in particolare gli

uccelli. Seduto in chiesa durante la sua commemorazione, continuavo a pensare, non potevo credere che fosse scomparso. Intorno a me le

donne piangevano e gli uomini sembravano fare di tutto per

trattenersi. Non pensavo fosse appropriato piangere, così non l'ho

fatto. Dalla sua tomba, ho osservato scoiattoli inseguirsi tra le

lapidi. Le foglie frusciare e cadere gialle, a scrosci, con il vento.

L'inverno stava arrivando. Un'enorme macchia scura di volatili

divideva il cielo sopra di noi. Erano ancora in migrazione. Allora ho

capito che il mondo sarebbe andato avanti anche se Il nonno non c'era

più.

Sue

mi amava moltissimo. Lei sapeva che io e il nonno eravamo molto

legati. Mi disse, con discrezione, che potevo piangere. Diceva di

sapere che dentro ero distrutto. Le risposi che stavo bene e che

presto tutto sarebbe tornato normale. Lei sembrò terrorizzata e non

mi parlò per il resto della giornata.

Mi

trovo, ora, davanti ai cancelli. Gli insetti tacciono. Ero qui non

più di due ore fa, ma sono passato oltre e sono tornato a casa.

Sento che ci devo entrare. Le nere lance in ferro battuto dei

cancelli e della recinzione puntano verso il cielo. Perché chiudono

i cancelli del cimitero? Chi vuole entrare, entra, e chi è già

dentro non può uscire. Immagino che il custode debba fare qualcosa

in più che semplicemente tagliare l'erba.

Sto

attento a non impigliare i vestiti mentre scavalco con l'aiuto

di un nocchiuto ramo di quercia. Un tuono rimbomba mentre atterro con

un sobbalzo dall'altro lato. Conosco la strada; l'ho percorsa mille

volte nell'ultimo anno. "Susanna Teal", recita la lapide.

Sotto ci sono le date di nascita e morte. Un anno fa, mia madre ha

ricevuto una terza chiamata in tarda notte. Sue aveva avuto un

incidente mentre tornava da una festa. Non era arrivata in ospedale.

Desidero

disperatamente dire qualcosa, ma ho la sensazione che il vento, che è

aumentato d'intensità, porterebbe via qualsiasi parola che potrei

dire. Per chi le direi in ogni caso? So che amavo Sue. Almeno sentivo

per lei ciò che ha significato l'amore nella mia vita. Mia madre

diceva sempre che io veneravo la terra su cui camminava, ma non ho

pianto al suo funerale. E la mia vita è comunque andata avanti.

All'improvviso

mi sento male. Quel poco che ho mangiato prima di camminare minaccia

di salire. Fisso la lapide e la motta di erba verde. Sto andando

avanti, sopravvivo.

Lo

stomaco mi si rivolta, e corro curvo verso il cancello mentre la

pioggia inizia a cadere. Si sente come un silenzioso ruggito mentre

la mia camicia, impigliata su una delle punte, si strappa. Sono

accecato dal vento e dalla pioggia mentre corro via da quella pietra,

da quei cancelli scuri, verso un bagliore d'acqua sfocata attraverso

il campo.

Picture by Laura ©

© 2023 - Laura A. Ferrabino

Once upon a time, there was a king who tied his shoelaces backward every Tuesday. His wardrobe was filled with a vast array of shoes!

Every Tuesday, he chose a different pair of shoes and tied the laces backward, showing his people that he, too, could make mistakes, but in the end, they could still trust him.

He strolled through the streets of the kingdom saying to everyone he met, 'You see? It doesn't matter how you do it; what matters is that what you do leads to a result in the end.'

King Kifezgalir (for that was his name) was a perceptive man who changed the fortunes of his people with cleverness and simplicity.

The End.

© 2023 - Laura A. Ferrabino

C'era

una volta un Re, che ogni martedì si allacciava le scarpe al

contrario. Un vastissimo guardaroba di scarpe!

Tutti

i martedì sceglieva un paio di scarpe diverso, e tutti i martedì

annodava le scarpe al contrario, per dimostrare alla sua gente che

anche lui poteva sbagliare, ma che alla fine si poteva comunque

fidare di lui.

Usciva

a passeggiare per le strade del Regno e ogni volta che incontrava

qualcuno diceva: "Vede? Non interessa come lo si fa ma importa

che quello che si fa ti conduca alla fine ad un risultato."

Re

Kifezgalir, era questo il suo nome, uomo perspicace che cambiò le

sorti del suo popolo con ingegno e semplicità.

Fine.

Picture by Tim ©

© 2023 - Timothy D. Capehart

(for

Alice Pearce and Bruegel)

“Phil—ip?”

Alex asked drawing his husband’s name out into two long syllables.

“A—lex?”

Philip mimicked.

“What

are you doing?” Alex asked though well aware of the answer.

“Looking

out the window.” Philip said matter-of-factly.

Alex

looked over his glasses and over the top of the book he was trying to

finish reading before his book club met. “I can see that, dear.”

he said although, over the top of his glasses, all his nearly blind

eyes could really see was a Philip-colored blob near the light of the

open window across the room. “Why are you staring out the window?”

“I'm

not staring so much as glancing in a lingering fashion.” Philip did

not even cast his eyes in Alex's direction.

“You

are being a Gladys.” Alex said pressing his glasses back against

the bridge of his nose so that Philip came into focus.

“Not

so much.” Philip paused. “I just heard something.”

“Yes,

well the neighbors are going to see you 'hearing something' if you

lean any closer to the screen.” Turning his attention back to his

book, Alex read, for the third time, a sentence he would soon

have memorized. At least he could quote that sentence at the book

club meeting.

“What

do you think he's doing?” Philip mused.

With

a sigh, Alex stuck his book marker in place.

“I couldn't say. Which

one are you watching today?”

“I'm

not watching... but it's Blondie. He's pulled his van up to his front

door again. He keeps walking back and forth between the van and his

house.”

“So

he's loading something into it.” Alex said as if he were talking to

an unreasonable toddler.

“He's

not carrying anything.” Philip said. He finally looked away from

the window. “And each time he goes in either direction, he looks

both ways like he's crossing the street...” Then with the gravity of

Sherlock Holmes revealing a startling deduction, he added, “Or

checking to see if anyone is watching him.”

“Someone

IS watching him.”

Philip

rolled his eyes. “He can't see me.”

“Don't

be too sure. I think you have a waffle pattern on the end of your

nose from the screen.”

Philip’s

fingers touched the end of his nose self-consciously before he could

stop himself. He looked daggers at Alex. “Well, this is my

neighborhood. I'm being vigilant.”

Alex

shook his head. “You’re being Gladys Kravitz. Someday a Samantha

Stephens is going to put a whammy on you for it.”

“Do

you think he's hiding drugs in his van? Maybe he's going to take them

downtown to sell them; but in order to be safe if the cops stop him,

he's hiding them in various places around the interior of the van.”

“I'm

sure that's it.”

“Your

sarcasm is far from helpful.” Philip said with a trace of

testiness.

“Why

would I help you surveil the neighbors?”

“We

live in a neighborhood watch area.”

“Ah!

And you're doing your civic duty?” Alex asked dryly.

“There's

that sarcasm again. Blondie is home all day, every day. He lives in

that big house alone; we think.” Philip paused and pulled a face.

“He could have someone tied up in the basement!” He shook his

head dismissing the thought. “When does he work? How does he make a

living? It's drugs. I’d lay odds.”

“Odd

is a good word, but I’d apply it to you. He probably works from

home, Mrs. Kravits. Leave the poor guy alone.”

“I’m

going to mosey upstairs,” Philip said as if the idea had just

occurred to him. “Maybe surf the Net.” He headed for the stairs.

“Yes,

the view IS better from the bedroom.” Alex called after him.

“Goodluck Gladys!”

~

Two

days later on the way home from a movie, Philip swerved the car at

the last minute narrowly missing a lamppost.

“I

knew I should have driven.” Alex said unclenching his hands from

the sides of his seat cushion.

“Sorry.”

Philip said. “Lighted windows draw my attention. I can’t help

it.”

“You

could just not look, Gladys.” Alex offered.

“I

said I can’t help it!”

“Well,

then don’t steer toward what you’re looking at!”

“I

can’t help that either.”

With

a healthy heaping of snark and an equal measure of emphasis, Alex

said, “Then just don’t look!”

Philip

changed the subject, “Speaking of being a Gladys…and I’m NOT—”

Alex

rolled his eyes, but kept his counsel.

Philip

continued, “I repeat: not being a Gladys…Madame Mayor—”

“I

wish you wouldn’t call her that.” Alex interrupted. “Sometime I

am going to slip and call her that to her face. She’s the only one

of our neighbors we actually speak to on a regular basis. You know

her name is Madeleine; call her Madeleine.”

Philip

sighed, “She acts like the Mayor of the neighborhood. It’s more

fun to call them all by nicknames.”

“You

mean it makes it easier for you to imagine our neighbors are engaged

in outlandish behavior if we don’t call them by their real names.”

Philip

pouted, “Have you always been this un-fun?” After a micro-pause

he continued with his story, “Anyway, Madame Mayor Madeleine had

some type of meeting at her place yesterday after you left for work.”

“I

should never leave you alone in the house.” Alex massaged the

bridge of his nose and considered ways he could change his work

schedule to always be able to run interference between his nosy

husband and their innocent neighbors.

“Quiet.”

Philip admonished. “I have to keep you abreast of events in the

neighborhood.”

“By

all means.” Alex said with a flip of his wrist. “Breast me.” "So

I was putting out the mail when a car pulled up across the street

from Madame Mayor’s house. Three grey-haired women got out and

seemed to sneak up to the house—”

“‘Seemed

to sneak’?” Alex broke in.

“Yeah,

they were moving all slow and cautious, looking every which way.”

“Well

if they were older ladies, they would move slowly and cautiously

crossing the street.” Alex offered sensibly. “Especially our

street; people drive like their tailpipes are on fire.”

“Yeah,

well several of these ladies were carrying long, thin boxes. The

window was open and I know I heard them muttering to each other.”

Philip turned to look at Alex and the car headed for the roadside

drainage ditch.

“The

road! The road!” Alex pointed in a panic.

Philip

corrected and then continued meaningfully, “I know I heard one of

them say ‘Mafia.’ I bet they had guns in those boxes.”

Alex

stared disbelievingly at Philip.

Philip

nodded sagely and the car swerved again.

Alex

corrected the car’s trajectory himself with a nudge to the steering

wheel, pointed to the road with a jab of his forefinger, and said,

“Oh YES! I’ve heard of them. The Blue Hair Mafia!”

“Really?”

Philip asked believing for only a second. “Oh, you’re joking.”

“No.

No. No.” Alex said facetiously. “Surely you’ve heard of Cosa

Bonviva!”

“You’ve really perfected this sarcasm thing.”

“You

inspire me.” Alex crossed his arms and turned toward his hubbie.

“All kidding and sarcasm aside, one day one of our neighbors is

going to catch you. They may not take too kindly to your prying into

their business…or making up outlandish stories about them.”

“How

do you KNOW the stories are so far off the mark?”

“Dayton might have its share of crime…but the odds are against there being

Mafia, white slavers, a serial killer, kidnappers, and drug runners

operating out of the one block radius around our house.”

“You

don’t watch the news do you?

Alex

patted Philip’s shoulder. “Thank you. You are the most amusing

person I have ever known.” He smiled and pointed to the road once

more.

~

The

next morning Alex knelt over the remains of a diseased rose plant in

the side yard. Its stems were brown and brittle but no less prickly.

He was trying to figure out how to get it out of the flowerbed

without disturbing the healthy plants on either side of it when he

heard the back door open and close.

“Hey.”

Philip said as he walked by. “I think I’m going for a short

stroll.”

Alex

dug around a mesh of roots trying to figure which belonged to the

dead rose. “Ehh,” he said not totally registering what Philip had

said.

“Back

before too long.”

“K.”

Alex grabbed the garden shears and snipped. He heard the gate

clang…and then the word stroll connected to the word exercise in

his head, and neither of those connected with Philip in any

meaningful way. Philip, who had the metabolism of a hummingbird,

thought of exercise as something that happened to other people.

“Crap!” Alex tossed the shears aside. “Philip!” he yelled.

When he got no answer, he called again, gave up, and headed for the

gate.

By

the time Alex made it to the front yard, Philip was making his way

down the sidewalk with the studied nonchalance of a four year-old

approaching an unguarded birthday cake. “Hey! Where are you going?”

“For

a little walk.” Philip said innocently. “Is there anything wrong

with that?”

“Cut

the bologna and come home.” Alex stopped planting his feet with

some finality, but Philip continued down the street.

“I

saw something...” Philip said quietly without turning.

“Well, you shouldn’t have been looking, AND I’m sure whatever you saw

is, in actuality, nothing like what you have formulated in your

head.”

Philip

stopped behind a tall hedge which straddled the property line between

their next-door neighbor’s, who Philip unkindly called “the

Joads” after the Grapes of Wrath family, and Madeleine’s. He

peered through a break in the foliage.

Alex

scanned the street behind them praying none of the other neighbors

were out and witnessing this blatant act of domestic spying. “Will

you stop peeping at Madeleine’s house and come home with me before

someone sees you and calls the cops.” Alex crept forward and looked

over Philip’s shoulder in time to see Madeleine’s front door slam

closed. “Was that her?” Alex said grabbing Philip’s shoulder.

“Did she see you out here?”

“Hush!”

Philip said. “I told you I saw something. I just want to check it

out.” He bent over so that he wouldn’t be visible from

Madeleine’s house and made his way along the hedge row.

“Where

are you going?” Alex whispered urgently. When Philip didn't answer,

he bent double himself and followed his husband up the hill. He got

to the top just in time to see Philip slip through the hedge. Alex

dove in after him and was further shocked, though he would not have

thought it possible, to see Philip crouching just under one of

Madeleine’s downstairs windows. “Philip, get back here!” he

hissed.

Philip

made a shooing motion behind his back with one of his hands, and

slowly stood to peer over the sill and into Madeleine’s window.

Alex

crab-crawled forward and yanked Philip to the ground. “I am going

to make sure you are placed in psychiatric care as soon as I get you

home.” He turned to see Philip had one finger of his right hand

raised commanding quiet. His left hand cupped his cell phone against

his ear.

Alex

could hear one ring through the cell line. Then Philip nodded curtly

and said, “I’d like to report a home invasion.”

“Is

that 911?” Alex shouted while trying desperately to also whisper.

“Hang up! Hang up!”

Philip

ignored him. “5562 Downeybrooke Road. Hurry please.”

“Don’t give them your—"

“Philip

Varley. Yes, ma’am, I live just up the street.”

“I

can’t believe this. I can’t believe YOU.”

As

he closed the connection, Philip said, “Will you stow it for once?”

“It’s one thing for you to make these stories up in our house, but to call

the police? How are we going to explain this to them? To Madeleine?”

At the sound of approaching sirens, Alex buried his head in his

cupped hands. Without warning, an ear numbing bang shook the house at

his back. Alex looked up. Two large men scrambled along Madeleine’s

front walk nearly tripping down her stone steps. They threw

themselves into a van at the curb that Alex hadn’t noticed on his

approach.

The

tires squealed and smoked before the van shot off up the street. It

didn’t get a chance to turn the corner, a police car rounded on to

Downeybrooke. The van slammed into reverse, but the cars parked on

either side of the street didn’t allow for easy turn-arounds. Both

doors flew open, and the two burley men hopped out before the vehicle

had even stopped. They headed for the bushes up near Philip and

Alex’s house.

Alex

became aware that his mouth was hanging open, and he closed it with a

quiet snap. “How—” was all he could manage.

The

right side of Philip’s mouth quirked up as did his right eyebrow.

“I was passing the window in the upstairs hall when I happened to

notice the van in the street. It sat there for a long time before the

guys got out. They didn’t look familiar nor did they like people

Madam Mayor would be chummy with. I didn’t actually know anything

until I looked in her window.” With a flick of his thumb, he

indicated the one he’d just peeked in. “I saw one of them

restraining Madam Mayor while the other pounded his fist into his

palm.”

There

was some distant cursing. They peeked through the hedge to see the

two guys face down on their lawn with their hands cuffed behind their

backs.

Philip smiled. “I better go talk to the police. You want to check on Madam

Mayor?”

Alex pursed his lips and squinted his hardest stare at his husband.

“Madeleine.” Philip conceded. “Do you want to go make sure Madeleine is all

right?”

“Thank

you,” Alex said. “And yes; I’ll see how Madeleine is. You go

talk to the officers before they start pounding on our front door

looking for you. That would terrify the cats.”

With the widest of smiles, Philip said, “See. No Gladys. Just Helpful

Neighbor.”

Alex

smiled back and clapped Philip on the shoulder as Philip turned

toward their house. “Yes, ok. You were definitely a helpful

neighbor today, but you, sir, are absolutely POSITIVELY Gladys every

day!”

“Do

you think this attack is in retaliation for something the Blue Hair

Mafia did last—”

“GO!” Alex said with a smile; he pointed up the street. As he rounded the

corner of Madeleine’s house, he shook his head. He knew he would

never live this down; and, for good or bad, Gladys was here to stay.

© 2023 - Timothy D. Capehart

(per

Alice Pearce e Bruegel)

"Phil―ip?"

Alex domandò, allungando il nome del marito in due ampie sillabe.

"A―lex?"

Philip lo imitò.

"Cosa stai facendo?" fece Alex, consapevole della risposta.

"Guardo

fuori dalla finestra." Philip rispose con fare serio.

Alex guardò sopra gli occhiali e oltre il libro che stava cercando di

finire prima della riunione del suo Club del Libro. "Lo vedo, caro." rispose anche se, dall’alto dei suoi occhiali,

tutto ciò che poteva effettivamente vedere attraverso i suoi occhi

quasi ciechi, era una macchia colorata di Philip vicino alla luce

della finestra aperta dall'altra parte della stanza. "Perché

fissi fuori dalla finestra?"

"Non

sto fissando ma guardando fissamente." Philip non volse neppure gli

occhi verso Alex.

"Ti

comporti come Gladys." disse Alex, spingendo gli occhiali

indietro sul naso in modo che Philip fosse meglio a fuoco.

"Non proprio." si corresse Philip. "Ho sentito qualcosa."

"Sì,

beh, i vicini ti vedranno sicuramente 'sentire qualcosa' se ti

avvicini ancora di più al vetro." Riportando la sua attenzione

al libro, Alex lesse, per la terza volta, una frase che presto

avrebbe memorizzato. Almeno avrebbe potuto citare quella frase alla

riunione del Club del Libro.

"Cosa

credi che stia facendo quel tipo?" Philip rimuginava.

Con

un sospiro, Alex mise il segnalibro al suo posto. "Non saprei.

Chi stai osservando oggi?"

"Non

sto osservando... ma è Blondie. Ha di nuovo parcheggiato il suo

furgone di fronte alla porta di casa. Continua a camminare avanti e

indietro tra la casa e il furgone."

"Quindi sta caricando qualcosa." disse Alex come se stesse parlando ad

un bambino capriccioso.

"Non

sta portando nulla." disse Philip. Finalmente distolse lo

sguardo dalla finestra. "E ogni volta che va in una direzione,

guarda da entrambi i lati come se stesse attraversando la strada..."

Poi, con la gravità di Sherlock Holmes che svela una deduzione

sorprendente, aggiunse: "O controllando se qualcuno lo sta

osservando."

"Qualcuno

lo sta osservando, infatti."

Philip

sollevò gli occhi al cielo. "Non può vedermi."

"Non

essere troppo sicuro. Penso che tu abbia una stampa a quadretti sulla

punta del naso per via del vetro."

Le

dita di Philip toccarono la punta del suo naso consapevolmente, prima

che potesse fermarsi. Lanciò ad Alex uno sguardo infastidito. "Beh,

questo è il mio quartiere. Sto facendo il vigile."

Alex

scosse la testa. "Stai diventando Gladys Kravitz. Un giorno

Samantha Stephens potrebbe lanciarti un incantesimo per questo."

"Pensi

che stia nascondendo delle droghe nel suo furgone? Forse ha

intenzione di portarle in città per venderle; ma per essere al

sicuro, se la polizia lo ferma, le nasconde in vari posti all'interno

del furgone."

"Si,

son sicuro che è così."

"La

tua ironia è lontana dall'essere utile." disse Philip con un

pizzico di irritazione.

"Perché dovrei aiutarti a spiare i vicini?" "Viviamo

in una zona di vigilanza di quartiere."

"Ah!

E stai facendo il tuo dovere civico?" chiese Alex con tono

asciutto.

"C'è

di nuovo quell’ironia. Blondie è a casa tutto il giorno, ogni

giorno. Vive in quella grande casa da solo; o almeno, noi crediamo." Philip si interruppe e fece una smorfia. "Potrebbe avere

qualcuno legato in cantina!" Scosse la testa, respingendo il

pensiero. "Quando lavora? Come si guadagna da vivere? Strano,

scommetterei sulle droghe." "Strano

è una buona parola, ma io la applicherei a te. Probabilmente lavora

da casa, Signora Kravits. Lascia in pace quel pover'uomo."

"Faccio un salto di sopra." disse Philip come se l'idea fosse appena

balenata nella sua mente. "Forse navigherò in rete." Si

diresse verso le scale.

"Sì,

la vista in effetti è migliore dalla camera da letto", gridò

Alex dietro di lui. "Buona fortuna, Gladys!"

~

Due

giorni dopo, sulla strada di casa al ritorno dal cinema, Philip

sbandò all'ultimo momento, sfiorando appena un lampione.

"Sapevo

che avrei dovuto essere io a guidare", disse Alex, allentando le

mani dai lati del cuscino del sedile.

"Scusami." disse Philip. "Le finestre illuminate attirano la mia

attenzione. Non posso evitarlo."

"Potresti

semplicemente scegliere di non guardare, Gladys." suggerì Alex.

"Ho

detto che non posso evitarlo!"

"E

allora non sterzare nella direzione in cui stai guardando!"

"Anche questo non posso evitarlo."

Con una sana dose di sarcasmo e la stessa enfasi, Alex disse: "Allora

semplicemente non guardare!"

Philip cambiò argomento. "Riguardo al fatto di essere Gladys, e io NON

sono―"

Alex

levò gli occhi al cielo ancora, ma rimase in silenzio seguendo il

consiglio.

Philip

continuò: "Lo ripeto: non essendo Gladys… Madame Sindaca―"

"Vorrei

che la smettessi di chiamarla così." intervenne Alex. "Un

giorno, potrei accidentalmente sbagliare e chiamarla con quel nome,

in faccia. È l'unico dei nostri vicini con cui parliamo

regolarmente. Sai che il suo nome è Madeleine; chiamala Madeleine."

Philip

sospirò. "Si comporta come il Sindaco del quartiere. È più

divertente chiamare tutti con i soprannomi."

"Vuoi

dire che ti è più facile immaginare che i nostri vicini siano

coinvolti in comportamenti stravaganti se non li chiamiamo con i loro

veri nomi."

Fece

boccuccia. "Sei sempre così poco divertente?" Dopo una

breve pausa, continuò con la storia. "Comunque, Madame

Madeleine, il Sindaco, ha avuto qualche genere di riunione a casa sua

ieri, dopo che sei andato al lavoro."

"Non

dovrei mai lasciarti da solo in casa." disse Alex, strofinandosi

il naso e considerando i possibili modi per cambiare il suo programma

di lavoro in modo da poter sempre intervenire tra il suo curioso

marito e i loro innocenti vicini.

"Silenzio." ammonì Philip. "Devo tenerti informato sugli eventi del

quartiere."

"Certamente,"

disse Alex con un gesto del polso. "Informami pure."

"Così stavo mettendo la posta fuori quando una macchina si fermò

dall'altra parte della strada davanti a casa della Signora Sindaca.

Sono scese tre donne dai capelli grigi e sembravano avvicinarsi di

nascosto alla casa―”

"Sembravano intrufolarsi?" interruppe Alex.

"Sìiii,

si muovevano lentamente e con cautela, guardando da ogni parte."

"Bene,

se fossero state delle anziane Signore, si sarebbero mosse lentamente

e con cautela attraversando la strada." offrì sensatamente

Alex. "Specialmente nella nostra strada; la gente guida come se

avesse il tubo di scarico in fiamme."

"Sì, beh, alcune di queste Signore portavano delle scatole lunghe e

sottili. Il finestrino era aperto e so di averle sentite bisbigliare

tra di loro." disse Philip voltandosi per guardare Alex mentre

la macchina si dirigeva verso la scarpata del canale stradale.

"La

strada! La strada!" Alex indicò in preda al panico.

Philip

si corresse e poi continuò in modo sensato, "So di aver sentito

una di loro dire 'Mafia'. Scommetto che avevano delle armi in quelle

scatole."

Alex guardò Philip con incredulità.

Lui

annuì saggiamente e la macchina deviò nuovamente.

Alex

corresse ancora la traiettoria della macchina da solo con un colpetto

al volante, indicò la strada con l’indice e disse, "Oh

SÌ! Ne ho sentito parlare. La Mafia dei Capelli Blu!"

"Davvero?"

chiese Philip credendo solo per un istante. "Oh, stai

scherzando."

"No.

No. No." disse Alex sarcasticamente. "Avrai sicuramente

sentito parlare di Cosa Bonviva!"

"Hai

davvero perfezionato questa cosa del sarcasmo."

"Mi

ispiri." Alex incrociò le braccia e si voltò verso il maritino. "Scherzi e sarcasmo a parte, un giorno uno dei nostri

vicini ti scoprirà. Potrebbero non prenderla bene per il tuo

ficcare il naso nei loro affari... o per inventare strane storie su

di loro."

"Come FAI A SAPERE che le storie sono così lontane dalla realtà?"

"Dayton

potrebbe avere la sua quota di crimini… ma le probabilità che ci

sia la Mafia, trafficanti di schiavi, un serial killer, rapitori e

trafficanti di droga che operano nel raggio di un solo isolato

intorno a casa nostra sono molto basse."

"Non guardi le notizie, vero?"

Alex

diede una pacca sulla spalla di Philip. "Grazie. Sei la persona

più divertente che abbia mai conosciuto." Sorrise e indicò

nuovamente la strada.

~

La

mattina successiva, Alex si inginocchiò accanto ai resti di una

pianta malata nel rosaio del cortile laterale. I suoi steli erano

marroni e fragili ma non meno spinosi. Stava cercando di capire come